Bird Songs and Dancing

Sounds and Movement of the People

Bird songs, travel songs, and a wide variety of dances were given to us by the Creator and by the Creator’s helpers. As Paul (Junior) Cuero noted, “A small bird (tekuk) sings to us and tells us about what we go through in life—there are always lessons to learn.” He also said, “The animals are teachers, we must listen to them, they are in our songs and in our dances.” He also tells us that the songs do not belong to him or to other Bird Singers; they belong to all the people and it is our responsibility to sing them correctly.” One singer from the late 1800s, (Chi-hoow, the great-grandfather of Torrie Burch [Miskwish] from Campo) took his singing very seriously and lived what is described as “the poor life” living in a small hut and avoiding non-Kumeyaay foods. To purify and cleanse himself he bathed at the old mud hot springs at Jacumba using native grasses and the hot muds.

Reportedly Hatakek a resident of Manzanita is the early 1900s knew all of the old songs including the bird songs and dances and the songs for the image ceremony (DuBois 1906:135). There are literally hundreds of bird songs even though as educator and Bird Singer Ral Christman says, “The songs were almost lost, they were hanging from a thread but we kept them.”

As pointed out by Hinton (1996:145) there are words and sounds in Bird Songs and other native songs that at first seem to be meaningless or nonsensical. But, in fact these words and sounds are what she calls vocables, words that are perceived by the speakers or singers as real and imbued with meaning. Often these are sounds or transformed words from another culture or language and as Junior Cuero notes, all of the sounds are important, they are all meaningful.

This is particularly true of dance songs where the chanting, rhythm, body movement is more meaningful that verbal meaning. In some cases these vocables are said to be in spirit language or animal language and it is not expected that humans can, or need to specifically understand the words. In peon songs vocables are often strategically sung out while the opposing players are contemplating their call outs to unnerve them (Hinton 1996:146).

KUMEYAAY DANCING AND SONGS HAVE ENDURED ACROSS THE AGES

Vocables are highly important in Kumeyaay culture and to other native people of California in spite of the fact that most traditional anthropologists have not even recorded them. Scholars such as Densmore (1932) in his studies of Yuma and Yaqui music chose to ignore these valuable sounds thus under-reporting the songs themselves and failing to understand the chronological depth and essential sacredness of the sound (Hinton 1996:150).

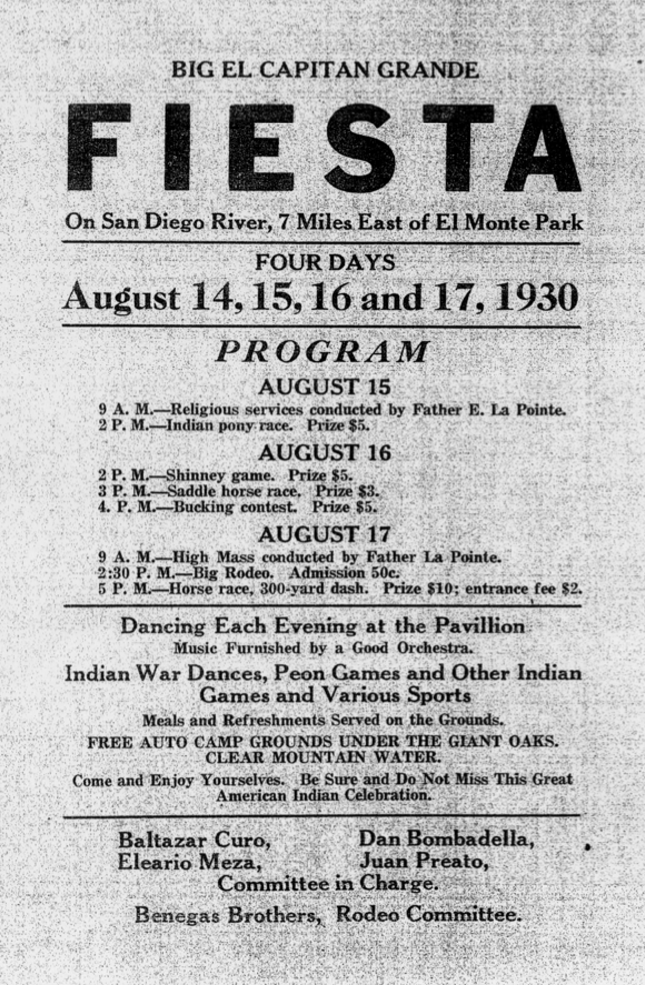

In the American period, Kumeyaay from many villages and reservations sponsored elaborate two or three day fiestas. These fiestas were a way from Kumeyaay of different clans to meet, to share food and materials, to dance the old dances, and in the early 1900s to generate income for the tribes. For non-Indians the yearly fiestas were a chance to gain a glimpse into Kumeyaay life and, in the heat of summer, to escape the cities and retreat to the cooler mountains. The pamphlet depicted below was a widely circulated flyer to entice people to attend a large annual fiesta at Capitan Grande in 1930.